I felt the need of writing this article in the aftermath of Malaysia’s 14th general election in May 2018 (GE14) when the second time Prime Minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad’s choice of Dr Maszlee Malik as the country’s Education Minister created controversy among some people. Dr Maszlee is a political scientist and an expert in Islam and contemporary issues with a decades-long academic career at International Islamic University Malaysia (IIUM).

The debate mainly concerned Dr Maszlee’s religiosity, not his ability to hold the education portfolio. One writer made it clear that she would not mind “politicians with religious backgrounds holding” portfolios other than education. Thus she pointed to a theory of binary relationship between religion and the cognitive realm.

A logical question that one could ask at that time is this: If someone with leanings to a religion other than Islam were appointed Education Minister, would there be any such unease about that person? The answer is possibly ‘no’. However, a simple answer may not be enough. We need to dig deeper below the surface.

Some people seem to have constructed a simplistic dualism between Islam and modern education. In fact, attempts to isolate Islamic teachings from learning processes and pedagogical practices are prevalent among a section of the educated gentry even in Muslim societies.

Critics of Islam seem to conflate Islamic teachings with ‘indoctrination’, ‘radicalization’ or ‘religious nonsense’ and consider Islam irrelevant (or even harmful) to the field of education. In all likelihood, such caricatures of Islam often heard in Muslim societies have arrived from far beyond their borders.

Also, these negative notions about Islam are perhaps based on the media hype surrounding unacceptable behaviors of some fringe groups. However, many commentators tend to forget that such self-labeling and extreme bunches exist in all religious and non-religious human communities.

Islam Is Relevant to Both Campus and Masjid

As an academic, I have heard stories where people simply dismiss any notion of discussing Islam at universities.

If someone shows interest in relating religion to various courses taught in classroom settings at mainstream universities, s/he will probably be brushed aside by lecturers or colleagues of different orientations. Some people may say: If you want to discuss religion go to church or masjid (mosque)!

I am not an expert in comparative religion and cannot comment on faiths other than Islam with comparable confidence, as I do not have specialist knowledge of and experience with them. What I can state clearly and with conviction is that, Islam is equally relevant to both campus and masjid.

In Britain, in late 2000, I attended a talk in which the speaker was a non-Muslim scholar who works on “bibliography of publications in European languages on various aspects of Islam and the Muslim world”. He told the audience that every year roughly 25,000 books were published on Islam in European languages (now, after eighteen years, the figure has perhaps gone up).

During the Q&A session, I asked him how it compared to a religion like Christianity. In response to my question, he flatly stated that no other religion in the contemporary world had received as much academic attention as Islam. This is a telling statement on the relevance of Islam to education and intellectual practices, especially in the current world.

Islam and Knowledge

Misgivings in respect to Islam’s relevance to education are common mainly among people – Muslims and non-Muslims – with inadequate knowledge about the religion and its history. It is important to know that Islam enjoins life-long education, as it makes seeking knowledge obligatory for its adherents – men and women – right from the cradle to the grave. In Islam, the act of acquiring knowledge is more highly valued than any other human activity. The search for knowledge is considered a form of worship and a jihad (striving for a worthy and ennobling cause).

Knowledge enables human beings to discover the truth, nurture the right attitudes and develop the desirable traits necessary to contribute to collective development. Perhaps, this is the reason why God commanded all prophets to acquire and spread knowledge. Importantly, reading or seeking knowledge is the first command of God ordained to Prophet Muhammad and through him to all humankind.

The Beneficial Knowledge

In Islam, education is a complete whole in itself that addresses all aspects of human life. Strictly speaking, the term ‘Islamic education’ is non-existent in the Qur’an, while the concept of ilm nafei (beneficial knowledge) is there in the Sunnah. So Islam encompasses in its own structure any knowledge that benefits its recipient as well as others and does not cause injustice (harm) to any. As such, Islam does not recognise the dualism of ‘religious’ and ‘secular’ education. As British writer Marmaduke Pickthall said in a speech he gave in Madras in 1927, “There was no distinction between secular education and religious education in the great days of Islam. All education was brought into the religious sphere.”

Generally, for instance, a subject like Fiqh (Islamic Jurisprudence) is considered ‘Islamic’ and political science, ‘secular’. However, Islam recognises no such bifurcation between knowledges. It accepts the validity of the concepts of revealed (divine) knowledge and acquired (human) knowledge, and embraces both as long as they are beneficial. In this respect, Pickthall stated:

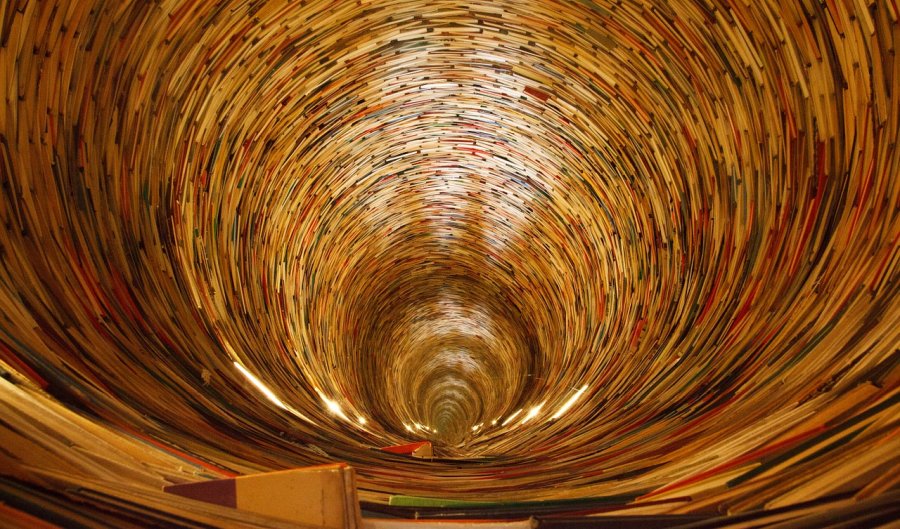

“Lectures on chemistry and physics, botany, medicine and astronomy were given in the mosque equally with lectures on [Qur’an, Hadith and Fiqh]. For the mosque was the university of Islam in the great days, and it deserved the name of ‘university,’ since it welcomed to its precincts all the knowledge of the age from every quarter.”

That is to say, as far as the dissemination of knowledge is concerned, in Islam there is not much difference between campus and masjid. Islam guarantees complete academic freedom and encourages all forms of learning as long as they serve the betterment of human life. So the educational practices that take place at campus can be replicated at a religious setting like masjid, and vice versa. In this respect, there exists a beautiful convergence between these two supposedly divergent entities.