Some people may imagine that the importance of the Black Box has declined recently, particularly after the frequent failure of investigations into the causes of some aircraft crashes.

But specialists continue to insist on its important role in determining the causes of the majority of air accidents, which have been on the increase lately.

The first thought of installing a device onboard aircraft to record the last moments of air accidents emerged during World War II, as a result of the rapid development in air navigation and the appearance of jet aircraft.

There were a large number of air crashes whose causes went unexplained, and air safety was endangered for reasons that were unknown at that time.

In 1954, David Warren of the Air Navigation Research Laboratories in Melbourne, Australia, thought of making a device that would record the conversations of aircrews and the readings of instruments.

The device he had in mind would be resistant to breakage and damage and could be retrieved after accidents, so that the information stored in it might help investigative teams in determining the causes of a crash. Warren published a report that year, but it wasn’t received with the welcome it deserved.

He decided to build a prototype of the device with the help of his manager, Tom Kippel, and his systems engineer, T. Merveller. They built the unit and named it “The Air Navigation Research Laboratories Flight Memory Unit.”

In making his prototype, Warren used a steel wire as a recording medium, on the grounds of it being fire-resistant and capable of recording up to four hours of the air-pilot’s voice and storing instrument readings at eight units per second. In addition to that it had the ability to automatically record over old material. This deemed it reusable.

The device was successfully tested in-flight and several aviation authorities were approached. Unfortunately, there was no favorable response.

In 1958, the Secretary of the British Air Registration Board, Sir Robert Hardingham, visited the Air Navigation Research Laboratories in Australia where he saw the Flight Recorder. Enthused with the device, he made arrangements for Warren to accompany him to Britain to present his prototype there.

British manufacturers’ response to the device was encouraging, and they provided the necessary support. Subsequently, installation of the Flight Recorder was imposed on all British aircraft. With the help of Alan Sirroken Frazer and Walter Bosol, Warren upgraded his prototype.

The improved Flight Recorder had a high degree of accuracy and recorded 24 readings per second. The British company, Sez Daval and Sons, obtained the production rights of the Flight Recorder.

In Australia, the crashing of a Fokker aircraft in Mackay, Queensland in 1960 led to a court order that all Australian aircraft carry Flight Recorders onboard.

An American company, United Information Control, developed the devices installed on Australian aircraft, using magnetic tape as the recording medium. But this tape wasn’t fire-resistant, and it delayed the development of the device.

However, the delay didn’t prevent Australia from becoming the first country to enact a law in 1967 making the installation of data and voice recording devices on its aircraft compulsory.

Nowadays, all aircraft are equipped with these devices that enable crash investigators to determine the causes of many aviation accidents.

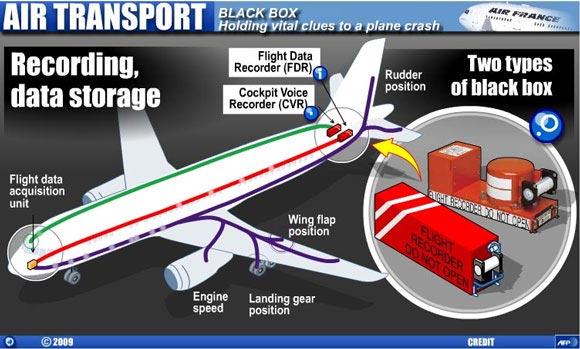

Flight Data Recorder

The early generation of data recorders used stainless steel tape or wire as a recording medium. The box housing the recording devices is made of titanium and lined with a heat-insulating material. The signals are received by various transformers and recorded on wire or tape every second in a repeated pattern.

In the United States, scientists used magnetic tape instead of steel. They were faced with a main problem: although magnetic tape afforded the advantage of storing data for longer periods, it wasn’t fire-resistant.

With the development of wider-body aircraft like the Boeing 747 and the DC 10, which could carry more passengers, there was concern over the occurrence of accidents that might not be explained because of the small number of variables used in recording.

This made the British government alter the specifications of data recording devices in 1967, so that the devices might record readings of between 17 and 32 variables per second. This would enable investigators to determine the causes of accidents with more ease.

Recently, flight data recording devices were developed to use solid-state units, so that they can store data in memories made of semiconductors or integrated circuits, instead of using electrical or mechanical means.

This is because this sort of devices doesn’t need regular maintenance or repair and enables the user to access information within minutes.

Current Specifications of Black Box

Recording time: 25 continuous hours. Number of variable readings: 5-30. Permissible collision: 3,400 grams/6.5 milliseconds. Fire resistance: 11,000 degrees/30 minutes. Resistance to water pressure: submersible up to 20,000 feet. Underwater site signal beacon: 37.5 kilohertz. Battery life: 6 years.

Investigators cannot determine the cause of an accident by using only the data recorder. If the conversations of the aircrew can be recorded and listened to later, investigators may be able to know the causes of a crash.

Hence the idea of recording conversations in the cockpit of an aircraft. The cockpit voice recorder records the conversations of the pilot and co-pilot, as well as air traffic control communications, announcements to passengers and any other sounds within the cockpit.

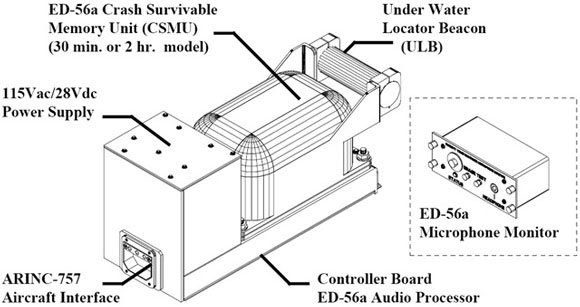

It works for thirty minutes continuously, which allows crash investigators to listen to the last half-hour of the flight and know what actually happened onboard the aircraft to draw a live picture of how and why the accident took place.

When the need arises to listen to the recorder, a panel comprising of representatives of the National Aviation Authority, the aircraft manufacturer and user, and the Pilots Association is formed. When the panel convenes, the members write a copy of the voice communications in the cockpit to be used by the board of inquiry.

A Fairchild voice recorder was developed for this purpose, and is now widely used. In the 800-plus air accidents that have occurred over three decades, these boxes were recovered in every case.

Information is stored in digital form so that it may be decoded easily. The voice recorder with the solid-state unit was developed more recently to fill the need for a larger memory.

In 1992, the voice recorder with the solid-state unit became available with a thirty-minute recording time. It was followed in 1995 by an improved version that affords a two-hour recording time.

Recording time: 30 continuous minutes (120 minutes for digital and solid- state recorders). Permissible collision: 3,400 grams/6.5 milliseconds. Fire resistance: 11,000 degrees/30 minutes. Resistance to water pressure: submersible up to 20,000 feet. Underwater site signal beacon: 37.5 kilohertz. Battery life: 6 years.

The devices are located at the rear of the fuselage, as the front part of the aircraft usually takes the brunt of a collision. This makes the tail and rear areas relatively safer. There are arrows on the outer surface of the fuselage indicating the location of the Black Box, where the two recording devices are housed.