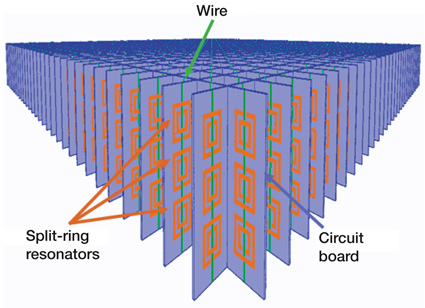

A new set of “metamaterials” has been created based on intricate, repeating patterns found in Islamic art. Metamaterials are engineered to have properties that don’t occur naturally, such as getting wider when stretched instead of just being longer and thinner.

These perforated rubber sheets made by a Canadian team do just that – and then remain stable in their expanded state until they are squeezed back again. Such designs could help make expandable stents or spacecraft components.

“In conventional materials, when you pull in one direction it will contract in other directions,” Dr Ahmad Rafsanjani, from McGill University in Montreal told BBC.

“But with ‘auxetic’ materials, due to their internal architecture, when you pull in one direction they expand in the lateral direction.” He spoke to journalists at the American Physical Society’s March Meeting, where the research was presented.

Dr Rafsanjani’s search for new designs to create such “auxeticity” found inspiration in the stonework of two 1,000-year-old tomb towers in his motherland Iran. “When you look at Islamic motifs, there is a huge library of geometries,” he said.

“On the walls of these two towers, you can find about 70 different architectures: tessellations and curlicue patterns.”

Two of those patterns in particular yielded an unusual combination of properties, when Dr Rafsanjani recreated them in a simplified form using a laser cutter and rubber sheets. Not only were these sheets auxetic – expanding in all directions when stretched – but they could snap easily back and forth between stretched and unstretched states.

Rotating Units

Such “bistability” is unusual in these materials, Dr Rafsanjani explained. Only a few other examples have been described, and they mostly use origami-like folding techniques.

Such “bistability” is unusual in these materials, Dr Rafsanjani explained. Only a few other examples have been described, and they mostly use origami-like folding techniques.

“These designs are easier to fabricate; all you need is a laser cutter. Depending on the resolution of the laser you could downscale your samples, probably to the micro scale. “Or you could upscale it for larger components like satellites or solar panels.”

He and his colleagues also found they could tweak the properties of the sheets by, for example, changing the basis of the patterns from straight lines to curved ones.

At the heart of the materials’ reversible change are small sections of the sheet that rotate as the rubber is stretched.

Rotating units like this – highlighted with colors in the images and video above – have formed the basis of many previous auxetic materials. But Dr Rafsanjani’s sheets are unique in the way they snap between configurations.

“We wanted to find structures for these rotating auxetic materials, [such] that when we deform it and it expands, it keeps its deformed shape,” he said.

This article is from Science’s archive and we’ve originally published it on an earlier date.

References:

- Jonathan Webb. Islamic art inspires stretchy, switchable materials. BBC. Retrieved in March 2016: http://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-35818924