AIDS have challenged modern lifestyles, fundamental hygiene practices and gender relations. As a result of the pandemic, US Surgeon General David Satcher, wishing to break the ‘conspiracy of silence’ surrounding human sexuality, urged for a national debate.

A lot of former surgeon generals have resigned after attempting to deal with HIV. Thus, Satcher produced a report that reflected America’s varied views on the subject.

The report asked for open discussion on abstinence, safer sex practices and contraceptives in schools. Elsewhere, a statement has challenged even the idea of contraceptives; a topic that arose at the end of a 6-day Southern African Catholic Bishops’ Conference in Pretoria.

The bishops felt that, “Condoms may even be one of the main reasons for the spread of HIV/AIDS. Condoms can be faulty. But, they contribute to the breaking down of self-control and mutual trust”. They cited a different reason for the spread of HIV and AIDS – the decline in circumcised men.

Allah gave us guidelines in the Qur’an for all our health practices. The Qur’an even addressed the spreading of viruses. While HIV and AIDS have become the leading cause of death among women aged 20 – 40 in Europe, sub-Saharan Africa and North America, the world’s HIV and AIDS drug industry continues to fail at finding a cure.

Meanwhile, drug resistant viruses have increased and debates continue over the health benefits of male circumcision. This, however, doesn’t change the findings of John and Pat Caldwell, who tell a frightening story.

With over 30 years experience in family dynamics and fertility control in Sub-Saharan Africa, the Caldwells began working on sexually transmitted diseases there in the 1970s, taking all existing theories into account.

The most popular theory is that the disease itself originated there. However, this theory contradicts the fact that AIDS cases were in hospitals of Uganda and Rwanda at the same time as they did in the West.

The only common factor in the spread of AIDS in Africa that the Caldwells found was the issue of male circumcision, which was generally unpracticed in the heart of the AIDS Belt – Central African Republic, Southern Sudan, Uganda, Kenya, Rwanda, Burundi, Tanzania, Zambia, Malawi, Zimbabwe, and Botswana (Caldwell, p.40).

In 1989, a joint Canadian-Kenyan medical research team at Kenyatta Medical School in Nairobi reported that during the previous year, the AIDS rate was higher among Luo migrants from Western Kenya than among the Kikuyu of Central Kenya.

The uncircumcised Luo men were more likely to have syphilis or chancroids – a sexually transmitted disease characterized by soft sores in the private area. They also had an unexpected elevated risk of contracting HIV (Caldwell, p.41).

An American team, led by John Bongaarts of the Population Council, also found that the regions across sub-Saharan Africa with high levels of HIV infection among local peoples correspond remarkably with the areas where men weren’t circumcised. The research drew upon statistics from the World Health Organization (Caldwell, p.44).

However, uncircumcised men in Tanzania didn’t need to wait for agreement among the researchers to come to their own conclusions. Based on their own observations of their community and of neighboring communities, they requested circumcision for themselves (Caldwell p.46).

Scientific Evidences

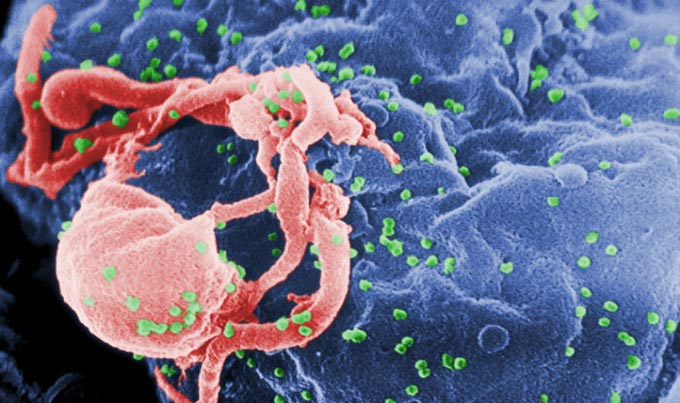

Epidemiological evidence points to the inner surface of the foreskin, which contains Langerhans’ cells that act as HIV receptors – a likely point of entry for uncircumcised men. A keratinized stratified squamous (scaly) epthelium (membranous tissue) covers the penile shaft and outer surface of the foreskin. This provides a protective barrier against HIV infection.

Epidemiological evidence points to the inner surface of the foreskin, which contains Langerhans’ cells that act as HIV receptors – a likely point of entry for uncircumcised men. A keratinized stratified squamous (scaly) epthelium (membranous tissue) covers the penile shaft and outer surface of the foreskin. This provides a protective barrier against HIV infection.

The inner mucosal (mucus) surface of the foreskin isn’t keratinized and is rich in Langerhans’ cells. During intimate relations, the whole inner surface of the foreskin touches vaginal secretions. Thus, it provides more area for HIV transmission.

Forty studies provide evidence that male circumcision protects against all sexually transmitted diseases. Circumcised men are also 2-8 times less likely to become infected.

Robert Szabo concludes that circumcision, as Islam teaches, would be the most immediately effective intervention for reducing HIV transmission since it occurs before men are sexually active (Szabo, p1-3).

Epidemiologist Robert Baily of the University of Illinois, Chicago, said, “No one wants to be the first to come out with a statement in support of male circumcision.” In the US and Europe, there are big anti-circumcision movements now, so people don’t want to promote something in Africa that is discouraged here…” (Shillinger, p.2).

Circumcised men come from communities that place a deep religio-cultural significance on this particular hygiene practice; which doesn’t necessarily apply to those who do not (Shillinger, p.1). The majority of Muslims believe that male circumcision is obligatory. It’s one of the five acts of cleanliness in Sahih Muslim, Sahih Bukhari, Musnad Ahmed and Sunnah at-Tirmidhi (Persaud, p.1).

There are also additional obligations of hygiene and social conduct within marriage. However, this doesn’t mean that Muslims are immune to AIDS. That’s since Islamic practices have become compromised by other factors. About 50% of Moroccan women who have AIDS have been infected by their husbands (Clinton, p.3).

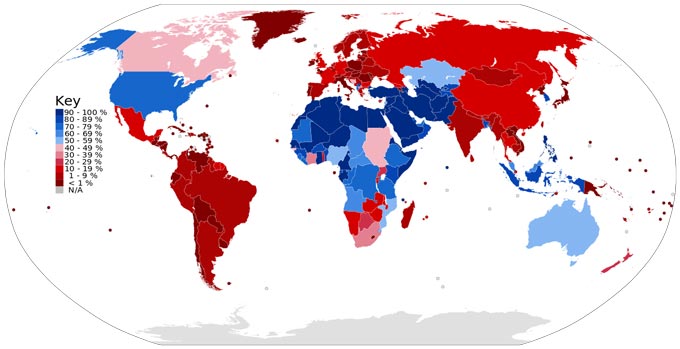

For now at least, the safest path to follow is one of cleanliness and purity, which modern science has confirmed. At the center of the hypothesis that male circumcision does provide a measure of protection against HIV-AIDS are puzzling discrepancies in HIV prevalence between different countries and regions, despite the presence of what seems to be similar risk factors.

For example, rates of HIV infection continue to be much lower in Asia’s Philippines (0.06 percent of the adult population), Bangladesh (0.03 percent) and Indonesia (0·05 percent), compared to Thailand (2.2 percent), India (0.8 percent), and Cambodia (2.4 percent).

Infection rates are also much lower in Africa’s Nigeria (4.12 percent), Ghana (2.38 percent) and Kenya (11.64 percent), compared to Namibia (19.94 percent), Botswana (25.10 percent) and Zimbabwe (25.84 percent).

It is this startling disparity between West and Southern Africa that has led researchers to conclude that the missing link is because unlike in Southern Africa, in much of West Africa circumcision is an ingrained cultural and traditional practice that has worked to keep HIV at bay.

There is no disagreement on the fact that AIDS spreads through sexual intercourse. The argument centers around protection men reportedly derive from the removal of the foreskin, to the extent that circumcision reduces infection by up to 50 percent.

Accelerating Researching

Global map of Male Circumcision Prevalence

Over 45 studies have examined the link between HIV and circumcision. Pro-circumcision researchers argue that the skin on the inside of the male foreskin is “mucosal”, similar to the skin found on the inside of the mouth or nose.

This mucosal skin reportedly has a high number of Langerhan cells, which are HIV target cells rich in white blood cells or doorway cells for HIV.

“HIV looks for target cells like the Langerhans; it’s a lock and key,” Edward G. Green, senior researcher at Harvard University told The Washington Times. “The rest of the skin on the penis is armor-like.”

Dr. Jimmy Gazi, who is acting-president of the Zimbabwe Red Cross Society and also chairman of the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) AIDS Scaling Committee, says that due to the “moist, mucosal surface” on his penis, “the uncircumcised male has a much higher chance of having a micro laceration in the glands and inside the foreskin than the circumcised male.” This exposes him to a greater risk of getting sexually transmitted diseases and HIV.

However, Gazi says that although circumcision is a good practice for those who subscribe to it, he would not put it as a major factor in hindering the transmission of HIV-AIDS.

It is now several decades since the first study on the increased risk of HIV infection among uncircumcised men was published. Since then, there were at least 45 scientific inquires to examine the link between HIV and circumcision.

One of the earlier investigations on the issue is a comparative study of four African cities conducted by UNAIDS in 1999. Two West African cities, Cotonou in Benin, and Yaounde the capital of Cameroon, had low HIV infection rates of three percent and four percent respectively among men aged 15-49.

The other two sites, Kisumu, Kenya, and Ndola in Zambia, had infection rates of 20 percent and 23 percent respectively for the same population group. In Cotonou and Yaounde, nearly all men in the study had circumcision. Only 10 percent of the men in Ndola and less than 30 percent of the men in Kisumu, meanwhile, had undergone the procedure.

Furthermore, the study found, ”HIV prevalence was below eight percent in men circumcised before their sexual debut and 25 percent in uncircumcised men.”

Despite studies like this, the medical body is still divided on the preventative benefits male circumcision might have. One thing that some anti-circumcision researchers point out is why the United States has the highest rate of HIV infection amongst Western countries while the great majority of the male population in the United States is circumcised.

Potentially, however, a pro-circumcision verdict within the medical community would allow for a relatively cost-effective mass circumcision campaign in much of resource-strapped Southern Africa where, according to the International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, “a gradual slide into destitution is underway which triggers further spread of HIV and ever-greater vulnerability to common disease and disaster.”

How to Fight?

The Red Cross adds that “the situation is slowly overwhelming Southern Africa and the longer-term projections are startling.” Such a grim prognosis on prospects for the region suggests that any new weapon in fighting HIV-AIDS would be more than welcome.

The Gaborone-based Botswana Harvard Aids Institute for HIV Research and Education says that if supported by clinical trials, male circumcision might be an acceptable method of preventing HIV transmission among adults and adolescents.

The institute has gone on to assess the acceptability of circumcision among adults and children through a cross-sectional survey at nine geographically representative locations in Botswana. Results show more acceptance of the practice if it’s for free in a hospital setting.

Among those who believe the virtues of male circumcision is important comes Dr. Mariam Esat, an infectious disease specialist based in Zimbabwe. She says part of the reason why there is a dearth of publicity on the perceived benefits of male circumcision is that “medical insurance (in Zimbabwe) doesn’t pay for it, certainly not adult circumcisions and not as a prophylactic against HIV.”

The Dean of the College of Health Sciences at the University of Zimbabwe, Professor Ahmed Latif, says scientific evidence does prove that circumcision in children allows the skin to keratinize (harden) like the back of the hand, thereby affording a great deal of protection against infections.

On the other hand, he says, the inner surface of the foreskin has mucosal membrane. This gives it a very large area of contact because of its folding. “We are very aware of the association between HIV and circumcision, but we are waiting for further confirmatory data,” Professor Latif says. “We know but we need to see more long-term studies.

“There is a link between alcohol and HIV infections. Thus, we should tackle this. But everything takes place slowly,” says Professor Latif.

Much like most things pertaining to HIV-AIDS, the link between the virus and male circumcision is still inconclusive.

References:

- com. “Women & the HIV/AIDS Epidemic.”Womens’ Issues-3rd World. 07/10/01.

- Caldwell, John & Pat. “The African AIDS Epidemic.” Scientific America 274: 3 (1996) 40-46.

- Clinton, Hilary, R. “Moroccan Women’s’ Roundtable Discussion.”S. Department of State Information. March 1999.

- Naqvi, Siki. ‘Ali, M. “A Manual of Islamic Beliefs and Practice.” The Muhammadi Trust of Great Britain & N. Ireland. 1991.

- Persaud, T. and Ahmed Mustafa, A. “Islamic Rules for Male Circumcision.”The First International Conference for the Scientific Aspects of the Qur’an and Sunnah in Islamabad, Pakistan. Islamzine.com. 08/14/01.

- Reuters Health. “Surgeon General Calls for Open National Dialog on Sexuality.” Reuters Medical News. 06/28/01.

- Reuters Health. “Drug Resistant HIV Spreading in UK.” Reuters Medical News. 04/12/01.

- “South African Bishops Condemn Condoms as ‘Immoral and Misguided.” Religious News Service. 07/30/01. Beliefnet.com 08/06/01.

- Shillinger, Kurt. “Male Circumcision Cited for Differing HIV Rates Among Africans.”org 05/11/99. 1-3.

- Szabo, Robert. “How Does Male Circumcision Protect Against HIV Infection.”British Medical Journal. 06/10/00.

- UNAIDS press release. Lusaka, 14 September 1999. “New research links dramatic HIV rates in girls to older partners”

- University of California, Center for HIV Information. “Viewpoint: Male Circumcision and HIV Infection: 10 Years and Counting.” Daniel T Halperin, Robert C Bailey. The Lancet, 354 (9192): pp. 1813-15.

- Health System Trust. Kaiser Daily HIV/AIDS Report 5/7/00 . Male circumcision – a defense against HIV?

- Kurt Shillinger, Boston Globe Correspondent, 11/05/99, Male Circumcision Cited For Differing HIV Rates Among Africans.

- The Botswana-Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership. Male circumcision: an acceptable strategy for HIV prevention in Botswana. P Kebaabetswe, S Lockman, S Mogwe, R Mandevu, I Thior, M Essex and R L Shapiro.

Editor’s Note: This article is from our archive, originally published on an earlier date, and now republished for its importance.