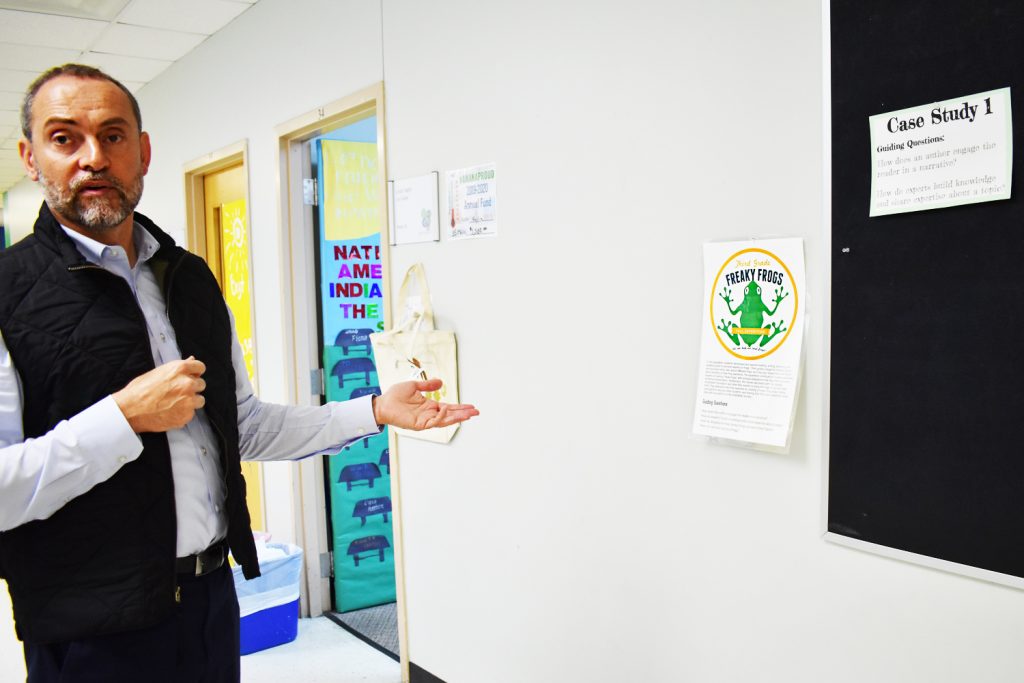

In the first part of this interview, Mr. Ehab Jaleel spoke as the executive director of Amana Academy. Away from his official position, we needed to know more about his personal opinions about raising kids in the United States.

As a Muslim parent of three daughters who experienced Islamic schools, public schools, homeschooling, and charter schools, he opens up on what he thinks is the ideal ‘American Muslim’ a parent should be raising and, thus, the kind of education parents should seek for their kids.

The Muslim American Father

AI: What kind of education should Muslim parents choose for their children? How do you balance problems with Islamic schools in terms of quality and public schools’ problems with ethics/bullying/lack of Islamic environment?

Jaleel: For us as a family, we sent our children to an Islamic school early on and all the way to third-fourth grade. There were a number of things we liked about it, but we felt it was a very insular environment. We knew there were schools that were doing a lot more in terms of community engagement, multidisciplinary approach, and project-based instruction. There was a lot of innovation happening in education. We didn’t necessarily see that for our kids, so we asked – what other options do we have?

When you think about your children, you are thinking, ‘how am I raising a complete person?’ I can’t say that for every Islamic school. I have been to some incredible Islamic schools, but resources are very important. The public school system has a difficult time recruiting teachers; there are thousands of unmet teaching jobs across the country every year. There is a teacher shortage in general. When you start considering the challenges the private schools, including Islamic schools, might have, such as not being able to spend the same amount of money, they are even more challenged in terms of hiring talented teachers and things like that.

If you look at our kids, they went to an Islamic school, they did homeschooling, we tried a regular public school in elementary, then we are here at Amana. Then two of my girls ended up in a hifz program in high school; they came out of that and went into a regular high school.

My current point of view is that one size may not fit all. You are going to go through different life stages in your child’s development that may influence what your school choices are going to be at that time. 20-40 years ago, when I was in school, we didn’t have choices. There was basically the public school. When we came to this country, my father tried to find the best public school, and my brother and I went to regular public school all the way through.

The whole concept of ‘Islamic school’ really came around in 1990; it happened all across the country. If you look statistically, I guarantee that no more than 10 percent of the general population is going to a private, faith-based school. The majority of the population can’t afford private schools; they go to public schools.

We have to be realistic about what is really possible. Right now, in Georgia, I guarantee that 95 percent of Muslim kids go to public schools. It’s a resource and funding issue. My youngest daughter goes to one of the highest-ranked public schools in the state; when you look at the resources they have, it is really amazing. It is very difficult to compete against that in a private setting.

I was talking to a leader of an independent, non-sectarian school, and he said that attendance in private schools is going down. They have a harder time filling seats in their schools, so they are trying new innovations to attract potential customers. Some of those innovations are creeping into public schools.

It is not just an Islamic school challenge; it is happening with other private schools, too. The difference is the population in non-Islamic schools is much bigger, so they can support those schools; they have a tradition, people have been giving for a long time, and there are endowments and so forth. So, it is a really long play.

AI: So, the obvious choice would be public or charter schools. What would you do, as a parent, in terms of the Islamic character of the kids?

Jaleel: In my observations, Islamic schools have to cover academics. So, the Islamic education happens in two ways: there is formal education as a period during the day and maybe Arabic once or twice a week, and you may have Quran; then it is just the “environment”. The teacher might say the word “subhan Allah”, or if the weather outside is beautiful and sunny, she might say “ma sha’ Allah”, or something like that. So, through the integration of Islamic philosophy and theology into the actual curriculum – only a few schools are really doing that well – is where there is actual, intentional integration.

There is that one program, Tarbeyya. I think it started in Ohio. The founder integrated Islam with regular education. So, I have to teach astronomy, how do I teach that through an Islamic lens? You have to develop the curriculum based on that. Otherwise, you are relying on the teacher, a really astute teacher who knows both sides of it. They know the scientific side, as well as what Allah (subhannahu wa ta’ala) says in the Quran and the Sunnah, and so forth.

AI: Is it more the environment or the education that makes parents choose Islamic schools?

Jaleel: It is not an integrated education. Parents are buying into the environment and they think, “My kids are around Muslims, and the teachers are all Muslims, and everybody is wearing modest clothing.” That’s great.

For me, having grown up in this country without any of that, we relied on the weekend school. There are a lot of untapped opportunities for after-school programs.

AI: Are you referring to the Sunday schools?

Jaleel: I am also talking about during the week. Look at the Roswell Community Masjid near here; we started a program on Quranic sciences. Three times a week, the kids are learning Qur’an after school.

My daughters learned full tajweed through that program, and we are ready to go on to the hifz program during the first couple years of high school. A year later, and they have memorized 6 juz’ and they can understand the Quran. I can’t. I can’t read as well as they read. When I lead them in salah, they are correcting me at the end of salah.

AI: Is there enough time to spend two hours after school?

Jaleel: They spend an hour.

AI: Is that enough?

Jaleel: I do not know if there is something more in the Islamic school, but that is what you have to ask yourself. At the end of the day, you only have a finite number of hours, and if you are going to teach high standards, teach Quran, plus those other subjects, we do not have enough time in the day now for regular education. Now we have to fit Islamic education into that – where do we find the time?

Do not get me wrong; it is very important for your readers to understand that I am very supportive of Islamic schools; I am very supportive of high-quality Islamic schools. I think this is the right choice for many families, but it is not the choice for everybody.

The other thing is on a personal level, I feel that we, as Muslims in America, need to be part of society and contributors to society. Our kids need to understand how to interact with this society. Interact in a way that isn’t based on fear but based on compassion and human experience. It goes back to understanding what I hear all the time from people of other faiths – they don’t understand Muslims. We need to understand them, and they need to understand us.

AI: Some people would say that Islamic schools create a bubble around the student, so when they go to college or high school…

Jaleel: I don’t know if we can make a general statement like that because it depends on the school. I think it depends a lot on the teachers and the administration of the school. I think some Islamic schools do a really good job with exposure to the community, and then others are all about the insular bubble. To me, that is not a recipe for success. I don’t think it grows the right kind of future leader of a company, academic, or a doctor. I think people need to understand how to work together.

When we think about solving society’s ills, it can be hunger, gun control, or wife battery; whether you are a Muslim or not, you want to solve those. Whether a person decides to believe in their faith, that’s up to them. To me, it is very important to us, as a family, that our kids are raised as Muslims and they have certainty about our faith and so forth. At the same time, I want them to be solving those issues with people of other faiths, because there is no way one percent of the population in America – out of 300 million people – is going to solve it all. It is not going to happen.

I’m all for high-quality Islamic schools that get the importance of preparing students for really active roles in society.

AI: So, the Islamic sessions outside of school are the ones you are relying on to give Islamic education to kids?

Jaleel: Absolutely. Listen, I am almost 53. I have lived the American experience completely, and I have traveled overseas to Muslim countries a lot. The conclusion I came to is that it is all about the family.

I’ve seen kids go through Islamic schools, become hafiz of the Qur’an, and then become atheists. I’ve seen kids in the best families, and then they become anti-Islam. Then I have seen other kids in regular high school, they went all through public school, and they ended up becoming amazing Muslims.

I think the family, the parents, have a real obligation to be active parents. To actually parent and not rely on any school, whether it is Islamic or public, or any teacher or anybody else. They should not hand over their responsibility, their Amana, of being a parent to an institution. They can’t do that.

To me, that is the failure.

Some very good families would send their kids to public schools, and they are not involved or watching what their kids are doing. Their kids become just like all the other kids who are dating, drinking, and partying. The parents are just blind; they have their heads in the sand, and they don’t know how to deal with it. What they are used to is ‘back home’, where it used to be the whole community, but now you are living in a country where you are only one percent of the country.

You have to arm your child with the tools to be able to manage and navigate that kind of society. Actually, not just navigate it but shape it. That is the challenge we have.