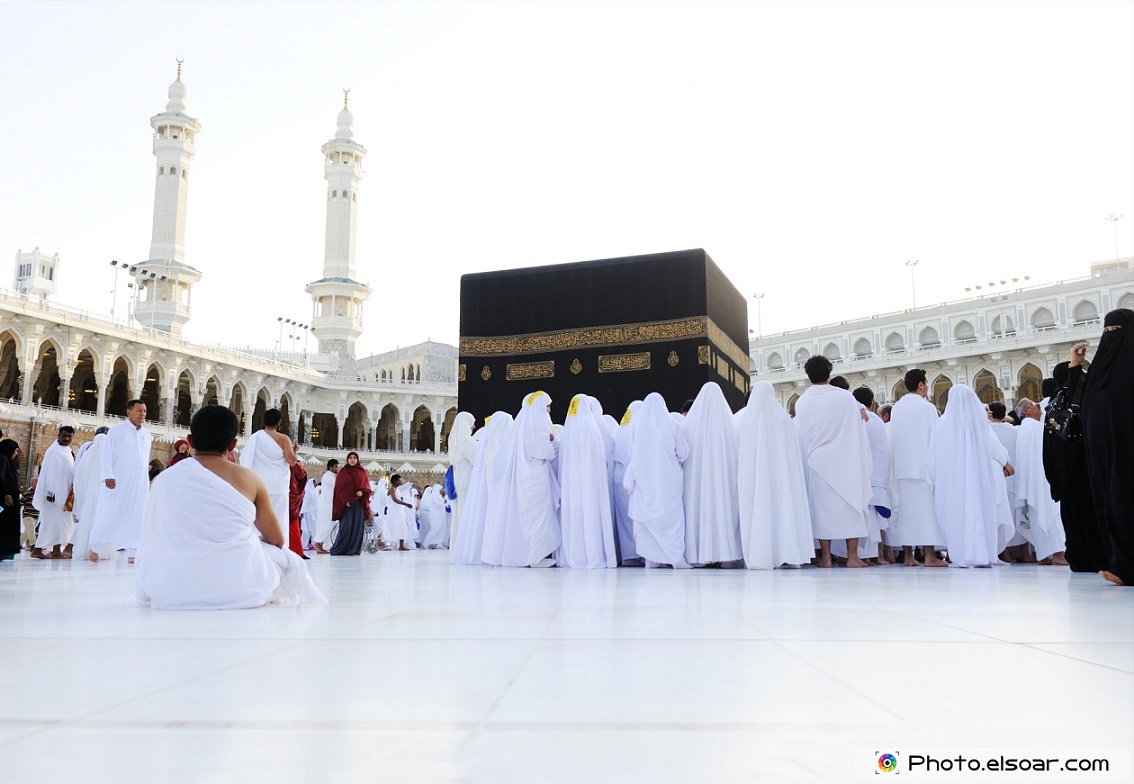

LONDON – During my last pilgrimage to Makkah, I had the good fortune of performing my spiritual rites alongside my mother. We entered the mosque together, we performed Tawaf around the Ka`ba together, we paused and prayed together, giving thanks to God. All around us, men and women did exactly the same, pausing, praying, in amongst one another. Gender was not an issue.

The last third of Ramadan, often viewed as the most spiritual time of the month to connect with our Creator, has led me to wonder about women’s access to our spiritual places.

For example, I read that during the time of Prophet Muhammad, sometimes, women would stay in the mosque for long periods of time, even sleep in the mosques (1). The famous scholar Imam Malik Ibn Anas said that it was preferable for women to perform itikaaf – enhanced spiritual prayers during Ramadan – in the mosque, stating specifically not to do so at home (2).

Ibn Qayyim and Ibn Hajr shared reports of women not only attending to itikaaf in the mosque during the time of Prophet Muhammad, but some were doing so during menstruation (3). And Ibn Qudmah shared that during Prophet Muhammad’s life, the mosque was full of rows of women lining up for prayers, and that when men would arrive late, they would pray behind women (4).

As I attended an iftar at one of the UK’s first mosques in Woking, it was strange to discover than I could not sit with the women in my life when we opened our fast as there was a curtain dividing men and women. This was very strange for me knowing that there were no curtains or walls dividing men and women during the time of Prophet Muhammad time, meaning that they would break their fast without division of genders.

Prior to Ramadan, I reached out to 15 of the biggest mosques in the UK asking them to advice on what services they will be offering women during the month of Ramadan, particularly, in the context of itikaaf. Only one mosque, in Chelmsford, responded, sharing that they have two classes for women every week, but do not have space for women to perform itikaaf.

They also ran a large event as part of the ‘The Big Date’ inviting neighbors which included community leaders, councilors, the local police and the BBC, to visit the mosque and to learn about Islam. – A great start, and very well done to them.

But in the absence of the other mosques responding, I then approached over two dozen British Muslim women about their local mosque experience and their plans for Ramadan. Most did not want to give a reply and of those who did, it was generally disturbing:

“I have no plan to visit the mosque during Ramadan.”

Kalssom B.

“I haven’t been in a mosque for years… Haven’t got a clue what they get up to and don’t really care to be honest.”

Shama R.

“I am not the best person to ask as I barely go to my local mosque!”

Remona A.

“Yes I plan to visit Palmers Green my local mosque. They do have space for women and they will hold events for women during Ramadan. I would also like to see pastoral services on offer.”

Aina K.

“The mosque closest to us has opened its doors to women during taraweeh this year. The mosque admin told my dad that it’s the first time ever. The room is quiet and peaceful, alhamdulillah, without the through of East London mosque, but would be nice if we didn’t have to use the side entrance that is home to three overflowing rubbish bins and another three recycling bins. #IsItTooMuchToAsk

Fareena A.

Mosques or Men’s Clubs

While some British mosques do accommodate women such as London’s Regents Park mosque and Woking’s Shahjehan mosque – both of whom were amongst those approached, but did not respond to my emails, on three occasions over two weeks – many British Muslim women still feel uncomfortable as mosques in our country are simply men’s clubs.

This was the first time I have experienced what it must be like to be a ‘British Muslims woman,’ in that I am an individual human being, I have a voice, I asked questions, raised my concerns, but was simply ‘ignored’ by mosque administrators. And while in some communities women are active in the mosque space, is it any wonder that so few British Muslim women, comparatively, are involved?

The mosque of Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) was not just a place to pray, but a social club allowing men and women a space. The early Muslims never had curtains or dividers to separate the genders. They had an understanding that while it is important to respect genders, it was equally important not to exclude genders.

One of the biggest traditions across the Muslim world is the performance of the taraweeh – additional night prayers – during Ramadan. Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) began this tradition, leading the congregation, but he then stopped leading the prayers in public saying, ‘Nothing prevented me from coming to you except the fact that I feared it would be made obligatory upon you.”

Prophet Muhammad actually discouraged the additional evening prayers (taraweeh) in public in mosques, preferring that it be something private, yet almost every mosque today offers them. At the same time, Prophet Muhammad stated clearly and repeatedly, to not stop women from going to the mosque, and we know from his tradition that women even performed itikaaf in the mosques, but very few mosques in the UK accommodate women.

As I ponder during the remaining nights of Ramadan, I wonder if as a society we will ever return to the Prophetic example of gender inclusion in our mosques in a way that gives everyday British Muslim women the option to visit mosques as regularly as female companions of Prophet Muhammad did.

We have thankfully, the example of pilgrimage in Makkah, where men and women today can pray in the same space without gender being an issue. Perhaps this should be a reminder and a guide for us all to return to the Prophetic Sunnah.

(1) Ibn Hajar, Fath al-Bari, vol 2 pp 101-102; Abu Shuqqah, Tahrir al-Mudawwanah vol 2 pp 181-194

(2) Sahnun, al-Mutanawwanah, vol 1 p 295

(3) Ibn Qayyim, Ilam al-Muwaqqin vol 3 p 26; Ibn Hajar, Fath al-Bari vol 4 p 810,818

(4) Ibn Qudmah, al-Mughni, vol 2 p 44; Abu Shuqqah, Tahrir al-Marah vol 2 p

195-202; al-Qayrawi, al-Nawadir wa al-Ziyadat vol 1 p 296; Sahnun, al-Mudawwanah vol 1 p 195