LONDON – In cooperation with Albukhary Foundation in Malaysia, a new Islamic culture gallery at the British Museum in London opened its doors to visitors on October 19, Financial Times reported.

“Roughly 1,600 objects are drawn from throughout the museum’s collection, replacing a Middle East-focused gallery that opened near the back entrance in 1989. Underlying the expansion, British Museum’s director Hartwig Fischer says, is a “new approach to Islam as a global phenomenon — one of the great spiritual, religious, intellectual and social phenomena of world history.”

The gallery, which spreads over two rooms, tells the story of the cultures of the Islamic World between the 7th century and the present day.

The Islamic World is a region of Muslim majority nations which stretch from West Africa to Southeast Asia, and from southwestern Siberia in Earth’s North Hemisphere to Central East Africa south of the Equator.

Albukhary Foundation Gallery provides an extraordinary opportunity for visitors to view artifacts presented in displays with themes such as science, calligraphy, fashion, and storytelling.

The Malaysian foundation is a non-profit organization with an international presence. For the past 40 years, it has been promoting goodwill through education and cultural heritage.

The new gallery’s collection also includes items related to archaeology, decorative arts, shadow puppets, textiles and contemporary art like medieval Egyptian water filters with geometric meshes and colorful glazes.

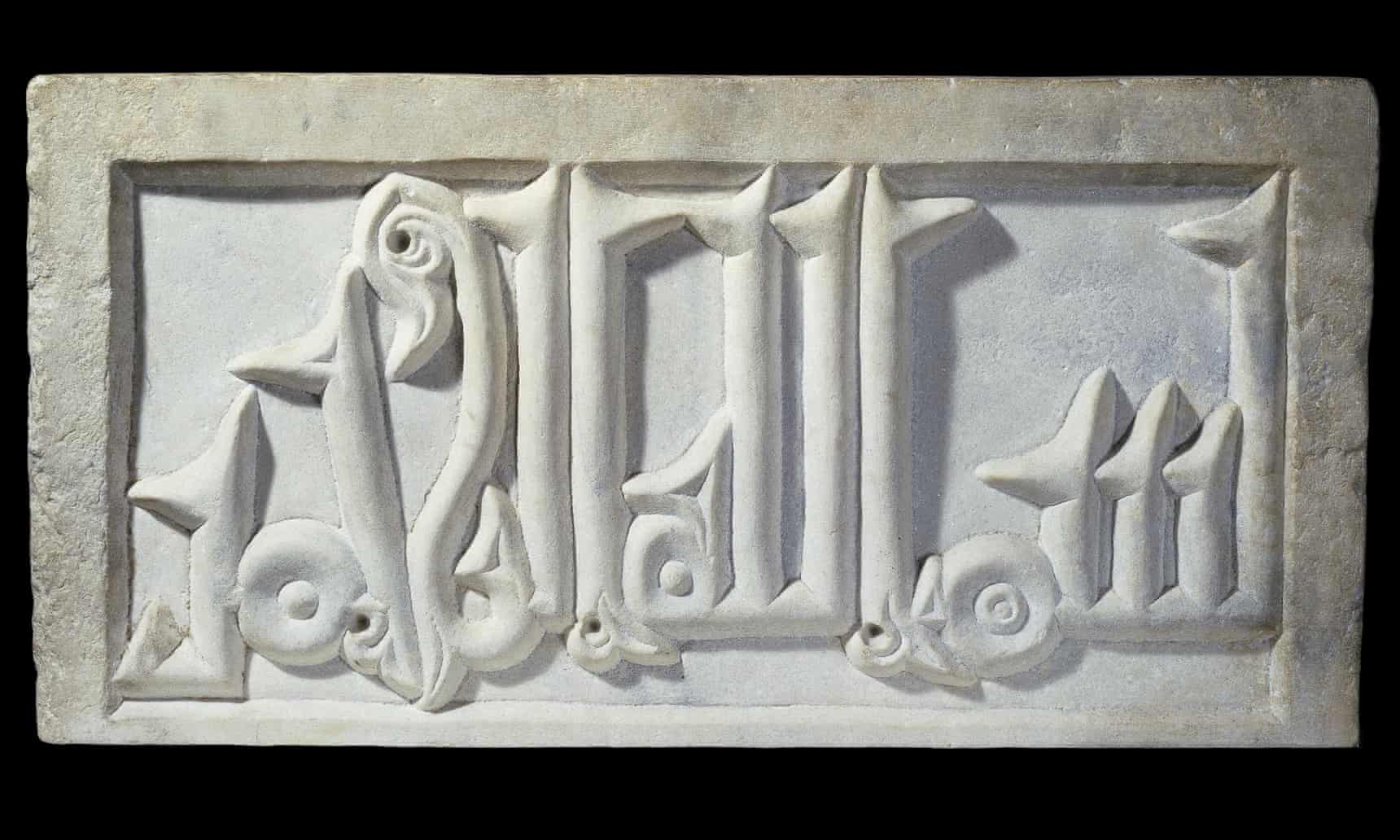

Arabesque … a stone inscription of early kufic script (c 967, Egypt). Photograph: © The Trustees of the British Museum

The launching of the gallery was celebrated with musical concerts, whirling dervishes and short plays that promoted Islamic culture.

Four years in the making, Albukhary has a team of six curators led by Venetia Porter and Ladan Akbarnia; co-authors of “The Islamic World: A History in Objects” which was published this month by Thames & Hudson.

“This gallery reflects the development, continuity, breaks, conflicting views of Islam and the large reality of interaction with other faiths. It makes a complex history much clearer, without reducing the complexity,” Fischer expressed.

He further explained that “it stretches notions of Islamic art beyond geometry and calligraphy or blanket terms such as arabesque imposed by 19th-century European art historians.”

“Figuration is everywhere, from Mongol star tiles with spotted gazelles to an Iranian palace spandrel with courtly horse-riders and European visitors in hats,” the director said.

“A large tile for an Iranian tomb, with Qur’anic script and a border of pale-blue birds, was not offensive when it was made in Kashan around 1308. Only later did an iconoclastic zealot see fit to obliterate the birds’ heads.”