Pakistani-American author, writer, and academic Asma Barlas visited London briefly on July 2, as part of her UK tour that will take her to the upcoming Bradford Literature Festival.

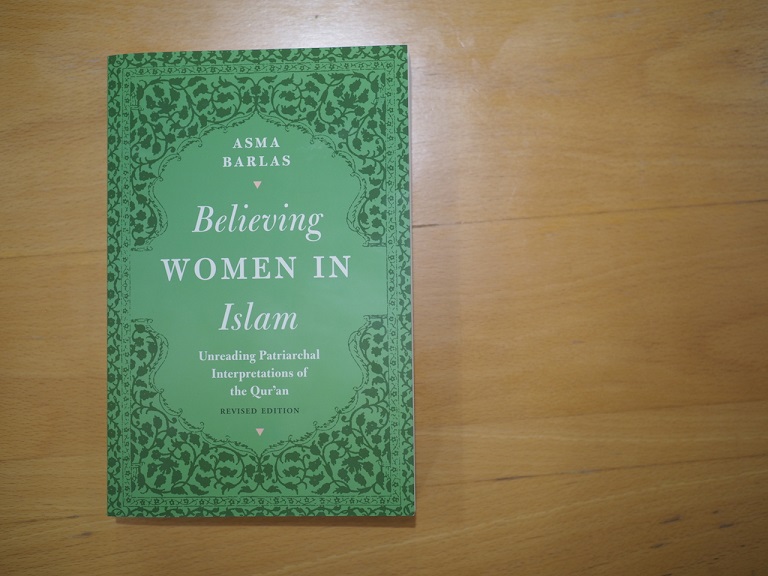

The author’s 2002 publication “Believing Women in Islam: Unreading Patriarchal Interpretations of the Qur’an,” propelled her onto the literary and spiritual scene.

Speaking at an intimate setting with a handful of British Muslim community activists, thinkers, writers and students, Asma spent three hours sharing her insight on gender and identity in the Qur’an, where she references religious texts to support the view that the Qur’an does not support male privilege, rather it refers and affirms equality of both genders.

This is a summary of the most fascinating points highlighted by Asma during her speech at Bradford festival.

How We Understand the Qur’an

“When I started to read the philosophy of religion, I started reading scholars of religion, so I read a number of people…I read Paul Ricoeur, a French philosopher. He speaks of hermeneutics as the theory, method, and philosophy of interpretation. In other words, how do we interpret interpretation…

“My contribution is not about you can read this verse differently to that verse because I’m not a linguist. My contribution is methodological. I have proposed a method of reading the Qur’an by the Qur’an which Muslims have always done, but I also make the argument – for which I am often severely attacked – that the Qur’an proposes its own hermeneutics.

“So what does the Qur’an say? It says the whole of it is from God, which I read as an argument for textual wholism. I can’t just pick up the Qur’an and cherry pick what I like and what I don’t like. If the whole of it is from God then I have to struggle with the whole of it. It’s a thematic whole.

“The Qur’an is replete with warnings to those who break it into parts, who shred it. The language can be quite strong. I read that to mean that you should not decontextualize it.

“One of the things that Kenneth Cragg points out is that the Qur’an speaks about the importance of contextualizing it. That context has to be central and fundamental to understanding its teachings. Context is to understand the historical circumstances in which specific ayahs were revealed.”

Asma Barlas with Mobashra Tazamal

The Importance of Context

“There were reasons why God spoke to human beings in a particular way. The Qur’an was revealed over many years, it’s not a linear text. So some of my Muslim friends who love to drink point to them. Tradition has it that when people turned up to prayers drunk then it was forbidden. So if you are not reading the whole in a particular way, if you are not looking for themes to connect them, you come to disjointed choppy contradictory readings of the Qur’an: how come it is saying this in one paragraph and something else in another.

“(E.g.) How can the Qur’an say to be kind to your wives if you are in the process of divorcing them, then why is it telling men that you can beat and strike your wife?

“What I say is that for Muslims the Qur’an is the word of God, so we should read it in light of who is the God that we worship. If God is Just, then God’s speech cannot teach injustice.

“There’s a congruence between Divine ontology, who God is, and Divine discourse, what God says.

“This is what I mean about hermeneutics, a method to read the Qur’an that looks for themes within it, so that is a belief I do not hold God to be contradictory, self-contradictory, unjust, unfair, I don’t believe that. So I have to struggle with my understanding of the scripture. If there is a contradiction there I have to find an acceptable way of trying to reconcile that.”

Asma Barlas with Aina Khan

Selecting Best Interpretations

“Understanding that language is not fixed, that text has multiple meanings and that just because we can read a text in different ways does not make all of the readings correct.

“One of the most profound things that the Qur’an says about itself is to search for the best of its meanings.

“(E.g.) There are passages that speak about Moses when God spoke to Moses to tell his people to hold fast by the best. And when it is talking to the Prophet it is saying to argue with your detractors in the best possible way.

“So to me the word ‘best’ suggests that it can have more than one reading, not all readings are equally good and that Muslims should have the freedom to pick and choose what they think is best, it’s a historically contingent argument as because notions of best are likely to change.

“The one problem of my argument is that the community of Muslims is patriarchal, so men are going to choose what is best.”

Is Wife Beating From Qur’an?

“There is a small book with a small but unfortunate title, it’s by Waqas Muhammad, it’s called ‘Wife beating in Islam? The Qur’an strikes back!’ He takes apart that verse in a way that is so brilliant.

“He goes back to Qur’anic Arabic and says that when you say to hit, to strike, you cannot just say ‘strike.’ In Classical Arabic, if you’re going to say ‘strike,’ you have to say ‘with what,’ it can’t be just ‘strike.’

“So I kept thinking what other passage says that. I remembered a passage about Prophet Job whose wife was foul-mouthed, and Job being a Prophet, vowed to strike her. And the exegetes believe that to allow Job to abide by that his promise, the Qur’an says to take in your hand some grass and strike her (38:44) So it’s ‘strike with’ some grass.

“Of course there are hadith which say that if you want to strike your wife to strike her with a miswak, but the point is that that is a hadith, it’s not in the Qur’an. The Qur’an is not saying to ‘strike your wife with.’

“The meaning of ithribu (to strike, from 4:34) it can mean to leave, to separate, to set an example, and here’s Muhammad (Waqas), it means to ‘cite’ to authorities. So he reads 4:34 by reading 4:35.

“It’s basically saying that if a married couple seeks a breach by themselves then it is ok for them to seek mediation. And if they still want to press on for a divorce then authorities need to be involved.

“So he is saying that it means to cite, in 4:34, as it is a continuation of the measures laid out in 4:35.

“He then asks, how can the Qur’an tell a husband to beat his wife (4:34) when the next verse (4:35) is saying if they want reconciliation (to get an arbitrator). What are the chances a woman wants to live with a spouse (who beats her)?

“In no other instance in the Qur’an, does the Qur’an say to do spousal abuse. For example, the verse which says that if you dislike a thing in your wife, it might be that you dislike something good for you (4:19). Then it says that if your wife and your children are your enemies, still deal with them in kindness (64:14)”

“We of course also know that Prophet Muhammad, upon whom be peace, never his any of his wives, so it seems strange for the Qur’an to endorse a form of physical punishment while the Prophet himself never engaged in any form of physical punishment or reprimand towards any of his wives. Could Asma’s interpretation of the Qur’an, therefore, fit more in-line with God’s wisdom?

The Qur’an on Gender

“There are three claims that the Qur’an makes about women and men that are eternal, not time-bound:

- We have created you from a single self and made you into nations and tribes so that you may know one another

- Women and men are God’s Khalifa (vicegerents) on earth

- Men and women are each other’s awliya (mutual guides: 9:71)

“These are teachings that are not contingent on time and place, they are principles.”

The Bradford Literature Festival

The most fascinating part of Asma’s speech was her ability to use the Qur’an to demonstrate fairness towards both genders. This theme fits in-line with wider principles and concepts of faith that center around a God who is Just, Fair, and Kind. Her book has recently been updated with an additional chapter.

Asma will join Rabbi Sylvia Rothschild and Rev Guli Francis-Dehqani at the Bradford Literature Festival on Saturday, July 6th. Their talk on Navigating Religious Patriarchy will no doubt be equally fascinating.