A few years ago, my oldest daughter played on a club soccer team. Between her numerous practices and games, I spent countless hours sitting on the sidelines, watching her play and occasionally chatting with the other soccer moms.

One woman and I really seemed to click. I could see right away that we had a lot in common, from our quirky senses of humor to our parenting styles. We even shared the same first name! One evening I went home and told my husband happily that I thought I’d made a nice new friend.

At the next practice, Laura and I sat together again and chatted companionably. Abruptly, in the middle of our conversation, she turned to me and exclaimed, warmly, “You speak English SO well!”

“Well, I am from Missouri, so . . . “ I replied, letting my sentence trail off.

“You’re from Missouri?” she asked, confused.

“Yep!”

“But, where are you from originally?” she pressed, looking flustered.

“Missouri. Nowhere else.”

“But, your parents . . . ?”

“Missouri.”

Clearly Laura had assumed that I was a foreigner. In fact, her assumption was so firm that despite my fluent and unaccented English, despite all our commonalities, including our shared name, and my assurance that I was born in the USA, she still could not reconcile reality with her preconceived notions.

The Headscarf

What led her to believe that I couldn’t really be American? It wasn’t the way I spoke or acted. It couldn’t have been my clothes, which were hardly exotic; the pants and tunic both came from a mainstream American store. It was, of course, my headscarf — the only thing that separated myself, Laura, from the other Laura. My hijab is twenty square inches of fabric that might as well be an impenetrable wall between me and some of my compatriots.

And that experience was certainly not the first time I experienced microaggressions. Rewind about a decade before I met Laura. I was a new Muslim, just getting used to dressing within Islamic guidelines. I also happened to be starting a new job at a prestigious university, so I had gone to an upscale department store and bought a women’s business suit. It was both modest and tasteful, and I felt that with a coordinating headscarf, I would look quite appropriate for my new life as a Muslim professional.

On my first day, my boss asked the secretary, Grace, to show me around the department and help me get settled in my office. Grace looked at me dubiously and then started speaking very loudly and clearly as she gave me the tour.

“HERE IS YOUR OFFICE. YOU’LL BE SHARING IT WITH AMY.”

“Okay, thanks,” I answered, purposely using a quiet, normal voice. But no matter how many times I responded to her statements in normal English, she apparently could not comprehend that I was a fluent speaker. She interacted normally with her other colleagues; it was just I who received her loud and deliberate dictation.

Like Laura, she had assumed I was a foreigner, despite all evidence to the contrary. Like Laura, she couldn’t seem to grasp reality even when it was staring her in the face.

Did either of those women harass or threaten me? Were they violent or cruel? No. In fact, I believe both women were basically nice people who made false assumptions about a woman with a headscarf.

Microaggressions Matter

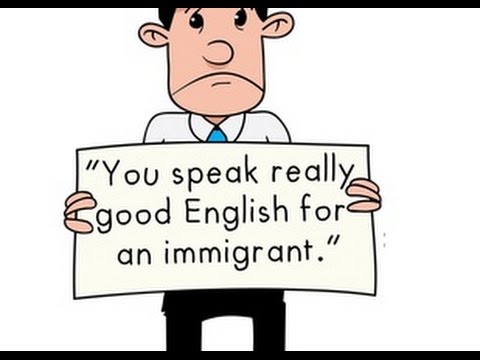

Considering the blatant acts of Islamophobia, violence, and harassment that some Muslims face, were the ladies’ insensitive comments such a big deal? Maybe not, but microaggressions– those tactless statements that stem from ignorance– are like erosion. Slowly, over time, they can wear people down, making them feel “less-than.” Less than American. Less than normal. Less than human.

In her article for The Atlantic, “Microaggressions Matter,” Simba Runyowa explains that microaggressions are “behaviors or statements that do not necessarily reflect malicious intent but which nevertheless can inflict insult or injury.”

She continues, “There are indeed some microaggressions that may not be worth interrogating or intellectualizing. The internet, in particular, has contributed to an exhausting cycle of retributive outrage that spins the smallest error into a scandal. But at the same time, microaggressions do not emerge from a vacuum. Often, they expose the internalized prejudices that lurk beneath the veneer of our carefully curated public selves.”

Speak up!

I believe that most people, like Grace and Laura, are not intentionally hurtful. A lack of education or minimal exposure to diversity are often the problems. Precisely because they mean well and have a good heart, people who are culturally tone deaf would probably want to be aware of their mistakes to avoid similar ones in the future.

That is why it is so important to speak up when we experience or witness a microaggression. It can be difficult to speak coherently and courageously, though, when an injustice occurs.

Whether it happens to us or to someone else, we tend to freeze and stumble for the right words. Fortunately, there are strategies that can help prepare us.

In her enlightening report “Identifying & Responding to Microaggressions,” Jody Gray, Diversity Outreach Librarian at the University of Minnesota offers many useful ways to address insensitive comments, including:

– Finding a way to pause before making assumptions or reacting right away.

– Deciding whether the particular incident is worth your time and effort.

– Modeling the behavior you want from the person you are confronting.

– Avoiding being sarcastic, snide, mocking, or arrogant.

– Keeping in mind the goal is education, not winning a point or making someone feel bad or wrong.

– Focusing on the event, not the person, to decrease the likelihood of defensiveness.

– Using yourself and your own stories of how you have “unlearned” misleading or inaccurate information.

Once we fully understand what microaggressions are, we will start seeing them clearly and, unfortunately, more frequently than we would like. At some point, nearly all of us will likely witness –if not personally experience — some form of microaggression. How can we be effective allies of people who are targeted?

In her essay “Allies and Microaggressions,” Kerry Ann Rockquemore cites a technique called “Opening the Front Door,” an acronym for the actions an ally can take when they witness an injustice:

- Observe: Describe clearly and succinctly what you see happening.

- Think: State what you think about it.

- Feel: Express your feelings about the situation.

- Desire: Assert what you would like to happen.

While it takes courage to speak up and face a possible debate or confrontation, Rockquemore points out that “Silence communicates tacit approval. Apologizing to the target afterwards adds insult to injury. The worst ex post facto response of all is asking the target of a microaggression to fix the problem.” Therefore, it is extremely important for those who wish to be true allies to address the source of the problem immediately and courageously.

I was not always prepared to recognize or correct microaggressions. In retrospect, I wish I had spoken plainly to Laura and Grace, using the techniques above to educate them and make my feelings known.

However, as much as I don’t wish to witness or receive any more microaggressions in the future, I can at least feel confident that I have the tools to handle them when they come. I can see myself as “engaging in “microresistance,” which Rockquemore defines as proactively working toward an equitable environment instead of reacting to an individual’s bad behavior.

If we all join the microresistance, we can make a macrodifference in the way people view Muslims in the United States.

First published: October 2019