Living with disability is always a challenge, regardless of the geographical location. But for a disabled person living in Palestine under Israeli occupation, the plight is almost doubled.

Medical Aid for Palestinians (MAP) is a U.K.-based charity that has been reaching out to the most vulnerable Palestinian communities for the past 30 years, striving to achieve the highest attainable standard of healthcare in hostile and difficult conditions.

In 2009, MAP established a disability program, funded by the U.K.’s Department for International Development and in partnership with Birzeit University’s Center for Developmental Studies.

The program aims to improve the quality of life for Palestinians living with disabilities. It also aims to advocate for their rights and to promote positive attitudes towards them in their communities.

Other meanings of disability

Latifa and Suleiman are two people participating in MAP’s program. Disability, they clarify, is not only the physical inability to do certain things but is also the restriction that comes alongside being born in a country that has been made disabled through occupation and international interference.

Before the introduction of MAP’s program for the disabled, Latifa and many others felt marginalized in their hometown of Gaza: they did not have access to disability aids or equipment nor were there specialists or doctors who could provide them with advice. Also, people with hearing impairments and the blind, for example, did not have access to a university education.

“We suffer double the sufferings of the people in Palestine, especially because we live in Gaza, which has been under siege for the past eight years,” Latifa explains. “Electricity is not available and having a physical disability you are still expected to go up to 5th floor, as even generators are not always working due to fuel shortages. I also have to walk long distances because of lack of fuel for cars.”

Latifa stresses that during the last war on Gaza, the sense of being in danger was more pronounced for people with disabilities because their chances of survival under such conditions are much lower. It is hard for them to leave their homes in order to seek shelter or to move from higher floors to the basement. Israeli bullets and bombs don’t differentiate between able-bodied people and the disabled.

The war resulted in an increase of physical disabilities among Palestinians. “Imagine you find yourself in a wheelchair overnight or you lose your eyesight and you don’t know why this happened to you or how to adapt to it, all simply because you are born Palestinian,” Latifa says. She explains that internationally banned weapons are used on Palestinians in Gaza.

“These are ordinary people who were not involved in the conflict. Plus mental health disability is also on the rise due to the psychological abuse that Palestinians have to endure on a daily basis because of the Israeli occupation,” she says.

According to MAP, over 87 percent of Palestinians with disabilities are unemployed and one third of them never marry. Over one third of Palestinians with a disability have never been to school whilst many do not use public transport as it is not sufficiently adapted to their needs. It is these practical barriers that make living with a disability extremely difficult under occupation.

MAP’s program for the disabled teaches and trains people with disabilities how to ask for specific rights. One of its aims is to change negative perceptions and attitudes of society toward the disabled, such as pity and sympathy, that limit their abilities to achieve.

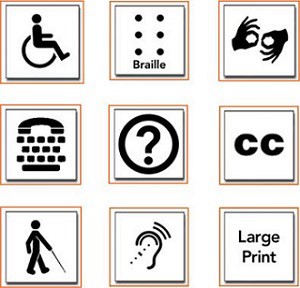

Another aim is to prepare the right environment for the disabled by providing ramps, braille books, induction loops and personal assistants, for example, without these aids being perceived as acts of charity from the state but rather their rights within their community. The program also strives to create equal opportunities for the disabled in the workplace. The ultimate goal is to help the disabled reintegrate into society.

Strength comes in numbers, so people with disabilities will have more of a chance to gain their rights if they unite at an organizational level. Latifa realized the importance of organizations and the importance of linking such organizations with one another and has participated in events and activities for people with disabilities.

Israeli occupation adds to the pain

After arriving in the United Kingdom as part of his participation with MAP, Suleiman says the experience he treasures most is the feeling of freedom. “For the last few days I have been experiencing the fantastic feeling of freedom. Arriving in London made me finally know the meaning of it, having tasted it for the first time at the age of 21 years,” he says.

Palestinians have been under occupation for more than 65 years. This prevents them from being able to interact with other countries, making them unaware of the opportunities and facilities available to people with special needs elsewhere.

Latifa said that men and women face their disabilities differently and that prejudice is doubled for a disabled woman. “We are not allowed to leave the house or go outside for fear of harassment and we are not even considered as suitable for marriage. A disabled woman represents a ‘problem’ that can be inherited through generations, someone who is not able to work/carry out duties, and who is not ‘the perfect’ model. Yet all religions on earth advocate equality,” she says.

According to MAP, over 87 percent of Palestinians with disabilities are unemployed and one third of them never marry.

Through MAP’s program, Latifa and Suleiman act as trainers, working with children in workshops and in the education sector. Suleiman has given more than 100 voluntary lectures and he hopes to teach people about disability and the meaning of freedom. Latifa, on the other hand, teaches children about disability and highlights words that hurt people with disabilities. She also works with families, training them to treat their children equally.

Suleiman is convinced that conditional funding and projects are not the way forward and won’t help the Palestinian people. “I am against charitable funding. I would like to see projects that can generate work, as I don’t want to rely on handouts. I want to be able to say I contributed to making something. This is how we are and we have rights because this charitable funding is demeaning,” he explains.

Latifa adds that organizations need to realize that the youth want to work. She would like to see projects that create real job opportunities and that are not a disguised ‘hand out’. She also believes projects should assess people with special needs and understand their full real needs: the physical, emotional and psychological.

As for who limits opportunities for the disabled more, the Israeli government or the Palestinian authority, Suleiman believes the Israeli occupation plays a major role. “It has not just taken our land but our thoughts, ideas and freedom.” But Latifa sees that the Israeli occupation, Palestinian authority and Palestinian attitudes are all connected.

In the past five years, she says, there have been two wars on Gaza resulting in casualties that needed to be treated outside Palestine, adding constraints on the Palestinian authority’s financial woes.

“We are simple human beings,” Latifa says. “We love like you. We smile like you. When we are hurt, we cry. And we long to have a family and basic things in life such as water, fuel and electricity. I long to live in peace and stop being labeled as a terrorist. I long for the day that Palestinians are not stopped at check points. When I came out of Gaza, I passed through Israel and I saw a bus full of Israeli children. I smiled at them and they smiled back for one simple reason, and that is we have one thing in common: humanity.”