MWLC2016 was the 2nd Annual Muslim Women’s Literary Conference, hosted by Daybreak Press and held at the University of Houston, Texas on October 22nd, 2016.

Created to provide a platform to celebrate, promote, and encourage Muslim women writers, MWLC is a fantastic initiative for the ever-growing niche of Muslim women with literary ambitions. As an offshoot of Rabata.org, the well-known Muslim women’s institute for traditionally based Islamic knowledge, those familiar with Daybreak Press are themselves of a more ‘conservative’ bent. This was reflected in the attendees, both in terms of numbers (to my eye, under a hundred people) and the general vibe.

While some may find this cause for complaint, I personally am quite happy to see conservative and orthodox Muslim women actively getting together and fostering such an environment for ourselves. Perhaps due to my social media bubble, many of the better-known Muslim writers efforts out there tend to come from the liberal/ progressive side (e.g. Muslim Writer’s Collective, anthologies such as Love, Inshallah and Salaam, Love) – and while I have no opposition to that myself (other than reserving the right to have my own differing religious views regarding certain issues), there are many who are reluctant to get involved because of their discomfort with such groups.

Daybreak’s MWLC provided a space for Muslim women to meet other Muslim women who have been able to achieve the elusive goal of being published, and to learn more from their experiences on how to hone one’s craft.

The goal of the conference was to critically look at the existing landscape of literature and how Muslim women are represented in both fiction and non-fiction; pitfalls committed by writers, particularly with regards to writing characters of color and various faith and cultural backgrounds; and the personal journeys and insights of Muslim women writers.

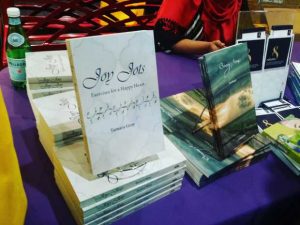

Anse Tamara Gray, Najiyah Maxfield-Helwani, Tayyaba Syed, Umm Juwayriyah, Asma Watts, Afshan Malik Writes, and Yvonne Maffei were just some of the powerhouses and panelists who organized and presented at MWLC 2016.

Shaykha Tamara invited us all to investigate the case of “the Mystery Lady” – the ‘Muslim woman,’ who is strangely absent or bizarrely flat in both fiction, non-fiction, and educational curricula.

Before anyone else, we must hold ourselves accountable – and it is grievous that Muslims have been responsible for erasing women from both our historical and current narratives. Touching on the lack of education about the Sahabiyyaat, Tabi’aat, and women of later generations of Islamic history, Anse Tamara presented examples from Rabata’s #SheIsMe project, an initiative created to highlight incredible Muslim women from every century of Islamic history along with the many, many female scholars, activists, writers, professionals, and artists who exist in our Ummah today and are contributing to society at large in more ways than we can imagine.

Fiction is another area in which Muslim women have been largely portrayed as victims, oppressed and in need of rescue by “white saviors” – if not overtly in the story itself, then in a sidelong, implicit manner by the authors themselves. The Breadwinner (by Deborah Ellis) was mentioned as an example of a Young Adult novel, popularly used in middle schools, and is often the first – and only – exposure that many North American schoolchildren will have to Muslim characters.

Islamic curriculums taught in Muslim schools are just as guilty of perpetuating male-centric narratives about Islam itself. As a professional in the field of education (she holds a master’s degree in Curriculum Theory and Instruction), Sh Tamara analyzed several popular Islamic curriculums taught across the country. To her dismay, none met the standard for demonstrating the inclusion of Muslim girls and women in their discussions on worship, history, or community engagement. Even elementary-level curriculums were devoid of Muslim girls in their illustrations, except on occasion to be holding a baby – yet never any depictions of girls as worshipers, activists, or shaykhas.

Challenges facing Muslim women

Ultimately, the lack of nuanced, authentic representations of Muslim women in both literature and educational curriculums is not something that we can blame on others, but which we must take responsibility for ourselves. By writing our own stories and getting involved in the field of education – which can be as simple as speaking to your child’s teacher or visiting your child’s class to give a short presentation – we can proactively change the narrative of “the Mystery Lady.”

“Savior in the Mirror” was the title of Najiyah Diana Maxfield’s talk, in which she tackled writing characters of different faith, race, and gender backgrounds, the pitfalls of lazy writing, and avoiding savior complexes.

To write three dimensional characters, there are three dimensions of research that writers must be aware of: non-Eurocentric/colonial history, cultural understanding, and worldview. To create authentic characters – especially characters of color – writers must think outside the box, step outside their own heads, and be able to view the characters’ world from their own perspective, with their history, their culture, their values, and their personality.

Storytellers need to establish an emotional connection to the characters and their history, presenting them as three dimensional characters rather than stereotypes and tropes. Lazy writing is indicative not only of poor writing technique, but of a lack of willingness to put in the effort to build a truly engaging and authentic story.

In the end, Najiyah Maxfield concluded, Muslims in the West have been given a platform like no other – with our faith and our community constantly in the spotlight, it is up to us to create our own place on that platform, representing ourselves and our narratives instead of being spoken for by and about others outside of our Ummah.

Umm Juwayriyyah, a pioneer in the genre of Urban Islamic Fiction, spoke about her journey from being a young African-American Muslim girl living in the inner city, to growing into a storyteller and finally, flourishing as a novelist. Witnessing the Muslim women around her invested in their communities, establishing their own narratives, and having strong foundations was instrumental to her growth as a person and as a writer.

There is great importance in finding one’s own story wherever one is – knowing that our experiences deserve to be spoken of. Winning writing contests, joining the school newspaper and covering sports events were all experiences that taught Umm Juwayriyyah that being an African American hijabi girl in the inner city did not mean that she was restricted to a certain niche, as a writer or otherwise.

Muslim women writers face another challenge – the idea that being “the ideal Muslim wife” excludes non-domestic interests, which has resulted in many Muslim women feeling as though they had to put their pens aside in order to please their husbands and raise their children. Umm Juwayriyyah’s experience taught her the opposite: that it is imperative for us to hold tightly onto our pens, for they are powerful, and part of who we are.

Being Muslims and being writers means that we must constantly ask ourselves what our purpose in writing is – and to draw upon our spirituality as a source of reminder, reinforcement, and seeking success through prayer and taqwa.

Finally, to really see a noticeable change in the literary about our communities, we need to invest in community building through literacy… beginning with reading to our own children at home, facilitating opportunities for them to develop their skills, and to feel as though their narratives matter.

These were just some of the topics discussed in the various panels, with entertainment provided in between by lovely munshidaat (nasheed artists) and incredible poets such as Asma Watts. Other panelists included Yvonne Maffei, author of My Halal Kitchen, who spoke beautifully about her adventures in faith, foreign countries, and food; Whittni B. Abdullah’s motivational presentation on the productivity of bees; and Tayyaba Syed’s deeply moving account of growing up as an immigrant in America, coping with Otherness as a person of faith and color, and growing into one’s own as a Muslim and a writer.

At the end of the panel, the question was posed: how will our writing impact our afterlife? Writing isn’t a lucrative career – we’re not in it for the money – so there are obviously greater, deeper reasons for it. Telling our stories can be done in numerous ways, including social media, but ultimately the intention must be a pure one: to give da’wah, to reach out and connect others to Islam in some way, however tiny.

Daybreak Press’s Muslim Women’s Literary Conference is a beautiful example of grassroots da’wah; a model of the incredible energy, talent, resourcefulness, determination, and success that Muslim women are utilizing to reclaim their places as dynamic members of the Muslim community, the field of literature, and the global stage. Though we may not all share the same perspectives on many different issues, it is necessary for us to recognize and encourage such wonderful examples of activism.

Now more than ever, when Muslims face higher political pressures and societal prejudices, we must hold firm to our faith and trust in Allah and forge ahead with renewed determination to reach out to those around us with our faith, our actions, and our words – both spoken and written. For indeed, we are commanded to do so by our Lord, the One Who taught humankind the use of the pen.